"A painter paints the appearance of things, not their objective correctness, in fact he creates new appearances of things. "-- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

More than mere observers, artists have fulfilled the vital tasks of interpreting humanity for centuries. Their creations have served to express the mood of a majority or to voice the quiet thoughts of a minority. Art has long been applauded for its unique reflection of societal growth . Art’s proactive campaigns, on the other hand, have not been as well recognized. The relationship between art and society is frequently oscillating—constantly trading off the roles of reactor and instigator.

The Bombs & Brushes exhibit is created with eye-opening, call-to-action, activist artworks in mind. The exhibit explores the art of revolution and the artists’ role as catalysts for societal change. By viewing artistic methods in the light of different social movements, one can observe how present art's influence can be. The strongest representations of a revolution may very well be symbols of both bombs and brushes.

The long trusted ingredient for social turnover and successful revolutions consists of a willing and able population as well thinkers who awaken and unite the masses. Intellectuals were afforded higher learning and were able realize the need and possibility for change (Hoppe, "Natural Elites, Intellectuals, and the State"). The saturation of novel ideas then spreads from institutions of higher learning to intellectuals. But, if the learned ideals clash with current social issues, intellectuals can turn into revolutionaries. These attitudes then proliferate among the common masses via available and plentiful art mediums. If not through physical distribution alone, the influence of artworks can be multiplied, extended, and reinforced through networks of people who exchange ideas and information with each other. Art not only reflects, it also influences and compels the population to heed to its message. “Art is the fountainhead from which…consequent actions ultimately spring,” says Murray Edelman, writer of book From Art to Politics: How Artistic Creations Shape Political Conceptions. “The conduct, virtues, and vices associated with politics,” notes Edelman, “come directly from art, then, and only indirectly from immediate experiences.”

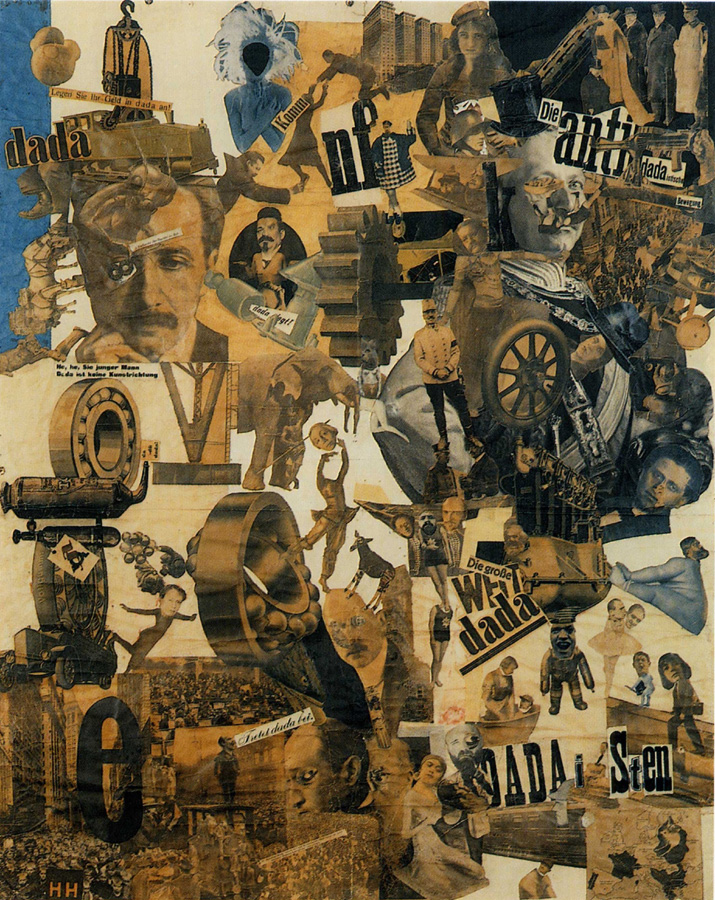

Demonstrably, artists and their creations have rallied the population for attention and change. The collection's chronology of events walks through a history of revolutionary art. Beginning with France in the late 18th century, art works have been a calling card for reformation. Notably, Jacques Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii (1785) delivered a clear message to the Intelligencias that the French Academy and royalty are weak and inept authoritarians. Similar paintings by David spurred futher dissent from the monarchy. Later on, The Army of Jugs (1793) and similarly mass produced posters were used to bond the French people against Royal rule. As time progresses, the rise of photomontages saw the creation of Höch’s Cut With the Dada Kitchen Knife (1919) and Heartfields’ The Butter is Gone (1935) which both rebel against the standing government in their own right. Finally, in the 20th century, artists such as Andy Warhol and Shepard Fiarey implemented repeated prints and posters to make a lasting impression about conformity.

The body of the Bombs & Brushes exhibit intends to publicize art’s deep involvement in ideological and social revolutions. The addition of music intends to further enhance the experience. Pieces played were out-of-the box for their time and embodied messages for change or social betterment. The power of art on revolutionary movements is undeniable and still as present in society today as it was centuries ago.

![Bombs & Brushes [Online-Mini Exhibit]](http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_N2w0Rlxs6U0/SpZvEFHJSnI/AAAAAAAAAHI/svrkp038I1M/S1600-R/bombs+gif.gif)